You know that feeling when you want someone close—but the moment they actually get close, something inside you recoils.

Or maybe you feel safer on your own—until the space around you gets so quiet it starts to ache, and suddenly you find yourself craving contact, wishing someone would just reach for you?

Welcome to the “claustro-agoraphobic dilemma”, a term coined by psychoanalyst Henri Rey.

At its core, this dilemma refers to a fundamental tension: the longing for closeness, comfort, and emotional safety that exists alongside the fear of being engulfed, overtaken, or intruded upon by the very people we need.

It shows up in therapy. It shows up in love. It shows up in our homes, our calendars, our clutter, even our furniture.

Why Do We Feel Trapped… or Alone… No Matter What We Choose?

From early in life, we use others—especially caregivers—as containers for aspects of ourselves that feel too much to hold alone. We project into them our neediness, our rage, our hunger for attention, our fears of being bad. And we hope they’ll survive it. Make sense of it. Offer it back to us in a form we can live with.

Sometimes we feel lost or abandoned if we’re too distant from those we imagine are holding the parts of ourselves we’ve projected outwards. After all, the projected parts of us, felt to be inside others, in reality are not.

And projection is a two-way street. Once we’re in a relationship, others begin projecting into us, too. And sometimes that feels invasive or destabilizing.

This is where it gets complicated.

We need our objects (in psychoanalytic terms: our emotionally invested others) because we can’t fully develop or hold our sense of self in isolation, and because we’re counting on them to symbolically hold our unwanted parts for us.

But once we become vulnerable enough to need others in this way, we become vulnerable to introjection too—to taking in their moods, needs, perceptions, or projections (often before we’re capable of making sense or containing them).

This can lead us to want to push away those very same people felt to be holding split off parts of ourselves. Because We don’t want to hold unwanted parts of them.

When it’s not just our own emotions we’re managing, but theirs too, we may feel trapped—with toxic contents inside of us.

This dynamic can feel physical too. We might have grown up in a cluttered home, or with a smothering caregiver who intruded into our space. Or maybe we experienced the opposite—too little contact from a parent who feared engulfment themselves.

As children, we may have found ourselves with no reliably comfortable position—whether we were trying to avoid excess or hungering for proximity.

The Manic Defense: Coping by Controlling

To avoid the pain of this “unsolvable” dilemma—the helplessness of needing others who might engulf us, or the loneliness of too much distance (and our fears that our aggression has destroyed our objects)— we often fall into defensive strategies.

One such defense, described by Melanie Klein, is the manic defense: denying or minimizing painful feelings of loss, guilt, or need by replacing them with feelings of triumph, control, or contempt. We flip vulnerability into power. Dependency into superiority. Grief into busyness.

We become busy instead of connected. Intellectually analytical instead of emotionally present. Superior instead of needy.

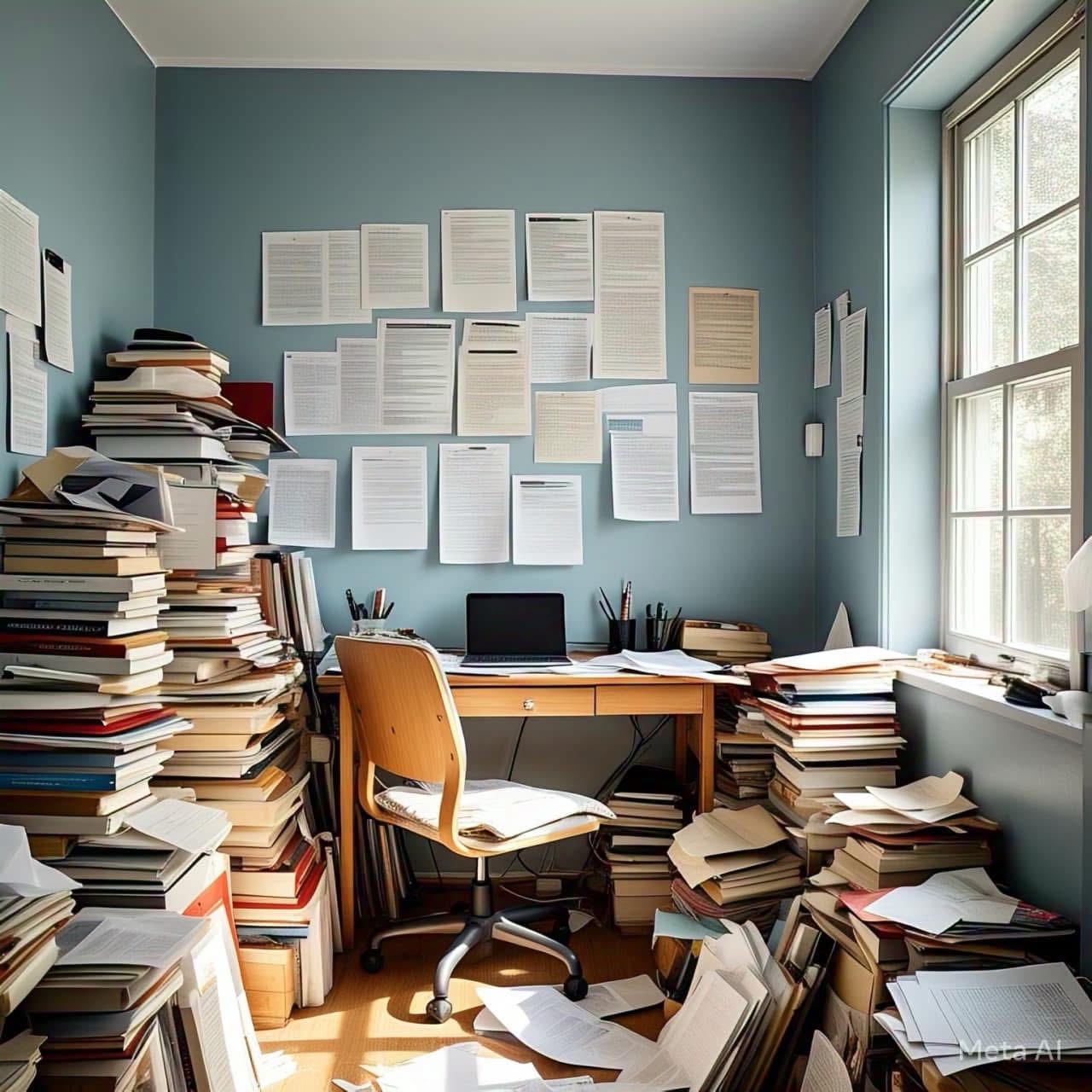

We clean the house rather than feel our longing. Or hoard objects that “hold” meaning and make us feel surrounded. Or avoid possessions altogether, for fear of being buried in clutter. Some of us say we want to get rid of our stuff, but we can’t seem to actually do it.

Physical manifestations of this dilemma

As I mentioned before, our relationship to our physical space can mirror our relational anxieties.

Some of us feel safest surrounded by our things—books, blankets, candles, mugs. Others feel suffocated unless everything is pared down. And some of us oscillate between the two, just like we do with people.

Our external environment often reflects our internal tension:

I want comfort, but I don’t want to be trapped.

I want space, but I don’t want to be alone.

In the Therapy Room… and Beyond

This dilemma plays out powerfully in therapy.

A client may come craving closeness, but if I respond with warmth, they pull back. Or they may keep me at a distance, then get hurt when I don’t break through their wall. Often what they long for is for me to know—without them having to ask. They want to be seen, but not intruded upon. Held, but not engulfed. Understood, but not interpreted too soon.

And I get it. Because don’t we all want that sometimes?

The work, then, is not to “solve” the dilemma but to name it. To notice it. To get curious about it instead of collapsing into it.

Sometimes that means grieving that no one can ever fully attune to us the way we imagine. Sometimes it means risking closeness anyway. Sometimes it means learning to hold the space between wanting and not wanting. And sometimes it means changing the physical objects we surround ourselves with or the space we embody.

Can We Learn to Stay With the Tension?

Over time, as the therapy relationship holds both sides of the dilemma, clients can internalize a new experience:

That they can approach without being swallowed.

That they can withdraw without being abandoned.

That they can want connection without it meaning they’re weak or childish or doomed to be disappointed.

And that they don’t have to tidy up the mess of emotional life with manic control or busy perfectionism just to feel safe.

Because in the end, we don’t want to be alone—but we don’t want to disappear either.

And if we can stay present to the parts of us that want both—connection and space, safety and freedom—we might discover that it’s not about choosing one over the other.

It’s about learning how to breathe in the space between.